Much of Michael Hersch’s recent music is situated around the frailty and destruction of the human body, whether it is terminal cancer in the opera On the Threshold of Winter, sketches of dying patients in End Stages for chamber orchestra, or confinement to a psychiatric hospital in the string quartet Images from a Closed Ward. And yet, in these bleak settings, Hersch somehow finds and communicates “a strange excitement,” to echo a phrase from Christopher Middleton, the poet featured in cortex and ankle. To journey into the darkness with Hersch—and the fearless interpreters who perform his music—is an invitation to experience the world in all its unfiltered, visceral intensity.

“a cascade of rough bark tearing your fingertips off

in a collapse of earth …” — Christopher Middleton

Hersch’s approach in the two pieces recorded here can be traced back to works he composed at the beginning of the new century, such as the wreckage of flowers for violin and piano (2003) and the ten-hour chamber cycle, sew me into a shroud of leaves (2001- 2016). A key presence in Hersch’s developing aesthetic was the British poet Christopher Middleton (1926-2015), whom Hersch met in 2001 during a residency in Germany. To shape the 50-movement, 145-minute arc of the first part (of three) of sew me into a shroud of leaves, Hersch included fragments of Middleton’s poems as written preludes to many of the movements. He intended no literal correspondence or “word painting” to link the music and text, but the lines of poetry provided points of anchoring and reflection for his own creative process, and also for the listener, who could follow along with the written text in the concert program or liner notes.

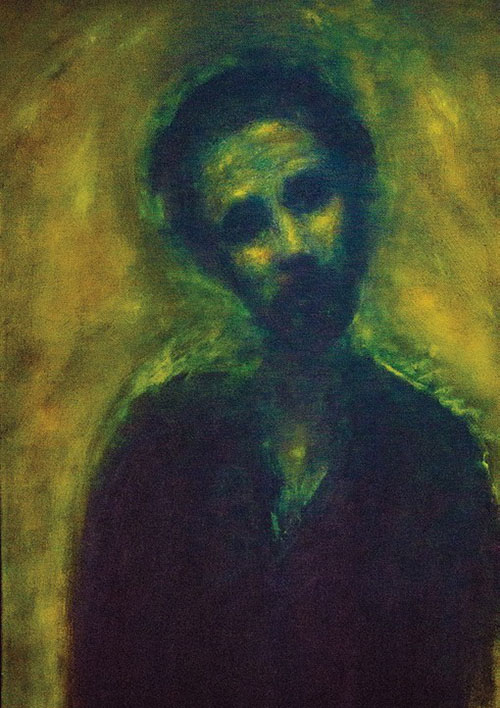

Hersch refined the process of pairing condensed movements with poetic fragments in A Forest of Attics (2009), of ages manifest (2011), and other instrumental works. He also extended the idea to the visual realm, linking movements to black-and-white etchings and photography in Images from a Closed Ward (2010) and in the twenty-two movements of his program-length work for violin and piano, Zwischen Leben und Tod (2012). The thread of music paired with art reached a new phase with Black Untitled, from 2013, commissioned by Ensemble Klang for a premiere in Amsterdam, and based on a painting of the same name by the Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning (1904-1997). Breaking away from the pattern of short and interrelated movements, Black Untitled took only one image as a point of departure for a stark and single-minded meditation.

As deeply engaged as he was with poetry, Hersch was reticent about setting words to music for a vocalist to sing. (A song cycle composed in 2010 for baritone Thomas Hampson was a rare exception.) “For most of my musical life,” the ever modest Hersch explained in an interview with the writer Marius Kociejowski, “I was convinced that the texts I responded to didn’t require anything other than their presence on the page, and that even if I wanted to engage it was highly unlikely I could have truly added anything to them.”

He broke his embargo in a most ambitious and impractical manner by writing On the Threshold of Winter (2012), a chamber opera sung by a lone soprano who contemplates death from terminal illness for two gripping, uncompromising hours. The work is rooted in the loss of a close friend from cancer, and Hersch’s own diagnosis and subsequent treatment for the disease. The opera’s premiere production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2014 added another key figure to Hersch’s musical circle: the soprano Ah Young Hong - the muse behind all of Hersch’s recent vocal writing. In 2015, she was joined by clarinet, horn and viola to introduce the song cycle a breath upwards (texts by Dante Alighieri and Ezra Pound); then in 2016, she appeared with Ensemble Klang for their second Hersch debut, cortex and ankle.

Bringing this entire creative chapter full circle, cortex and ankle marked Hersch’s first vocal setting of texts by Middleton, a year after the poet’s death at the age of 89, and fifteen years after their first inspiring encounter in Berlin in the fall of 2001. “It was a surreal juxtaposition,” Hersch recalled, “being in the midst of what was for much of the world, broadly speaking, a time of violence and disquieting uncertainty, and of beginning to see a way forward as a composer. The scaffolding for that increasing clarity was Christopher’s poetry. I don’t know if it would have happened without him, but it happened in that moment and in many ways everything I have written since stems more from Christopher’s influence than from any other artist.”

Hersch’s works for Ensemble Klang certainly align with his tendencies over the last fifteen years, and yet there are important new elements at play, most obviously brought on by the ensemble’s unique configuration. “He writes for us in a way that nobody else has,” noted Ensemble Klang’s Pete Harden. “The tremendous enjoyment for the group in performing these works has come from that sense of freshness ... These works go beyond personal expression, or attempting to provide collective catharsis. They’re deeply physical works, fleshy and corporeal, and while being expressionistic they still create all this room for the listener.” Harden singled out Hersch’s “unflinching outlook, one that even when the music is so sparingly written can leave the listener gasping for breath.”

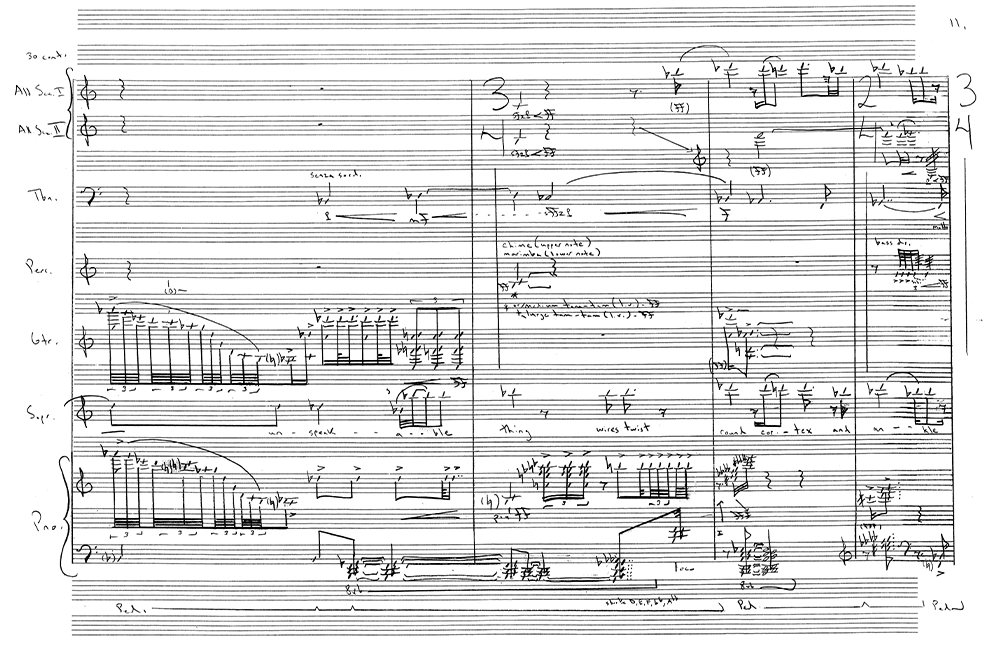

As a preface to the songs of cortex and ankle, a short instrumental prelude begins with adamant counterpoint that fades to hovering stasis, as if a premonition is foreknown and then lost. The arrival of the first song and its pale, chant-like utterances establishes the fundamental bearing of this work: direct, unsentimental, sparing in its use of vibrato and ornament, more a ritual of sound and space than a progression of pitches and rhythms.

Hersch’s manner of approaching poetry is to isolate the word fragments that speak to him, rarely setting an entire poem. For the interrelated songs of cortex and ankle, the texts establish an overall trajectory of descent. The early songs are upright and expectant, with several undefined figures that “walk forward beneath the living branches” in the first song, and a hesitant sense of waiting in the next song in which “the souls might one by one set sail.”

The fourth movement is an important musical juncture, its new clarity matched by a tighter visual focus on the fine-grained details of “needles of juniper,” “a sunlit white stone wall,” and a “tress of ivy” that “clings to the roof.” An oscillating pattern in the piano provides momentary grounding for the harmony and pulse. Key words repeat, their meanings altered by the increased urgency and jumpiness of the musical material. We are, without a doubt, “near oblivion.”

All the foreboding and downward motion coalesces in the fifth movement. The music begins with quiet objectivity, belying the gory imagery of “a cascade of rough bark tearing your fingertips off / in a collapse of earth.” The juxtapositions of light and dark are strident and extreme: “hurting, flayed, the light’s body a human sees with love, / opening a mouth in horror at the moon.” The music mirrors this quality of brutal proximity, often placing the singer a half-step or a minor ninth away from adjacent voices. The friction of these unstable intervals—not quite unison, or just overshooting an octave—aches with tangible, vibrating tension. (The ability of soprano Ah Young Hong to hold her ground amid such fierce sonic entanglement makes it clear why Hersch has entrusted her with so much of his recent music.)

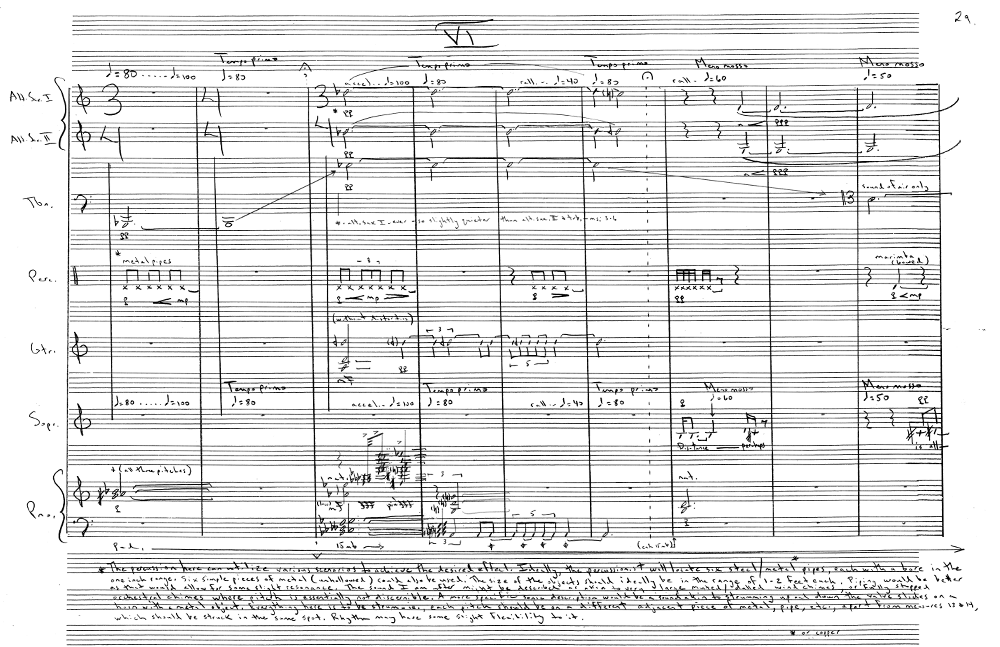

The sixth movement makes a momentary retreat: “Distance perhaps / is all for the best,” the text begins. The percussionist’s clanging metal pipes and the vocalist’s microtonal adjustments enhance the sense of disorientation.

The seventh movement returns to a mode of chant-like incantation centered upon several shocking images of “so much blood in the wind,” and the woman, “whose nose they cut off.” By the end, the musical texture reduces to nothing but a strong, rhythmic whisper. This leads to a flashback of sorts, when snippets of text and the piano’s oscillating pattern return from the fourth movement. At that earlier point we were “near oblivion” but still unaware of the form it would take; having now descended further, there is a nostalgic innocence in those earlier touchstones.

The next two songs migrate to the core of cortex and ankle. The ninth movement brings the only appearance of the self-revealing pronoun “I” in the text, within an image of a stairway rattled by one harrowing outburst. Then we go even deeper into a devastating view of mass graves, the vocalist reduced to a semi-spoken monotone punctuated with silences.

The final movement acts as a merciful epilogue, pulling us gently back toward centeredness with music that evokes pre-tonal liturgy. Incorporating text from Middleton’s translation of Charles Mauron’s Poem on Van Gogh, the closing image is one where the “heavens wheel and wheel,” witnessed from the “center point where all is at an end.”

Aaron Grad is a composer and writer based in Seattle, Washington. He provides program notes for the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and New World Symphony, and his music has been commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra and North Carolina Symphony.